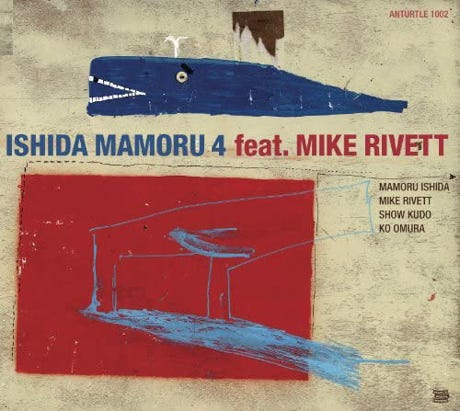

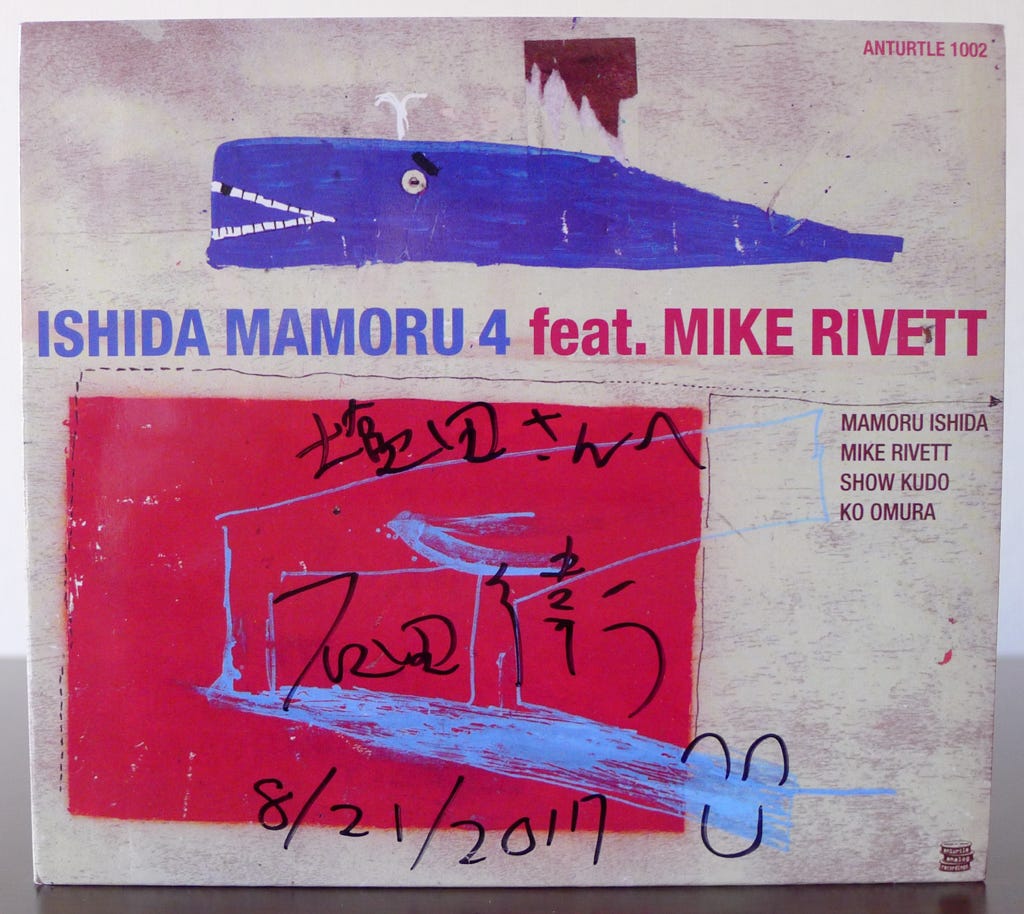

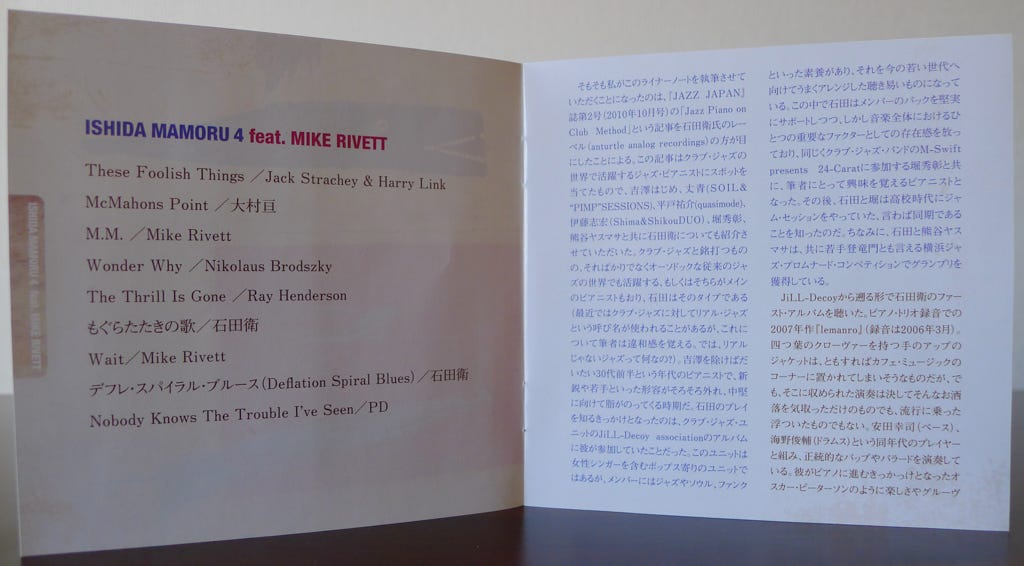

Mamoru Ishida: Ishida Mamoru 4 feat. Mike Rivett

Pianist Mamoru Ishida’s second album is titled Ishida Mamoru 4 feat. Mike Rivett and was released in 2011. With nine tracks over fifty-two minutes, the album presents a mix of covers, standards, and original compositions. The warm ballad “These Foolish Things” invites listeners in comfortably with a nostalgic calm, introducing a graceful jazz combo that respects traditional forms and songs loved by jazz fans.

The music as a whole expresses this vintage, sincere jazz feeling generated by the players’ sensitivity as well as through the recording methods and equipment used. While this can seem to be something of a jazz throwback album (meant in a good way, a sound that can be set comfortably alongside favored music of the past greats), there are also several aspects of modern, assertive jazz making appearances as well… not to mention the Japanese and international context also layered in, described well in the excellent and extensive liner notes.

Liner Notes

(Translated from the original Japanese liner notes written by Mitsuru Ogawa.)

Originally, I was asked to write these liner notes based on an article that I wrote for the second issue of Jazz Japan magazine (October 2010) entitled “Jazz Piano on Club Method”, which was noticed by the owner of Anturtle Analog Recordings, the label for which Mamoru Ishida records. That article spotlighted jazz pianists active in the world of club jazz including Hajime Yoshizawa, Josei (Soil & “Pimp” Sessions), Yusuke Hirado (Quasimode), Shikou Ito (Shima & Shikou Duo), Hideaki Hori, and Yasumasa Kumagai, all of whom I introduced along with Mamoru Ishida.

Although labeled as club jazz, they are not limited to that as they are also active in or mainly play in the style of the orthodox jazz world. Ishida is one of those types of pianists. (Recently, the term “real jazz” has been used in contrast to club jazz, but as an author, I feel a sense of discomfort with that. What is jazz that is not real?)

Except for Yoshizawa, most of these pianists are in their early 30s, and the description of them being up-and-comers or young players fell away as they started to mature into mid-career players. As for Mamoru Ishida, it was his participation on the album from the club jazz unit Jill-Decoy Association that introduced me to his playing. This is a pop-oriented unit featuring a female singer and members playing skillful arrangements with elements of jazz, soul, and funk, all factors that are appealing for today’s younger generation. In this group, Ishida provides solid backing support but also has a strong presence, important for the music as a whole.

As a writer, I developed an interest in both this pianist and Hideaki Hori, who was a member of the club jazz band M-Swift Presents 24-Carat. Later, I learned that Ishida and Hori had joined jam sessions in their high school years and were of the same generation, so to speak. Incidentally, both Ishida and Yasumasa Kumagai have won the Grand Prix prize at the Yokohama Jazz Promenade Competition, which can be considered a gateway to success for young musicians.

Tracing backwards from Jill-Decoy, I listened to Mamoru Ishida’s first album, a piano trio record from 2007 titled Iemanro, (recorded in March 2006). The cover depicts a close-up of a hand holding a four-leaf clover, seeming like something that may end up in the “cafe music” section, but the performances contained therein were stylish and original. Together with players of the same generation Koji Yasuda (bass) and Shunsuke Umeno (drums), they performed conventional bop and ballads. The fun and groove of Oscar Peterson, who inspired him to progress on the piano, can be felt in his performance. Also, a sensitive lyrical touch a la Bill Evans, powerfully sharp playing, and gentle, emotion-rich playing all skillfully coexisted in this one album. Yet, it could have been said that there were not many fresh or innovative elements, and the album may portray a rather plain impression overall. I can’t deny that some aspects were unsatisfying or that there could have been more energy of youth displayed, but these days many younger people don’t play in an overly-glaring way. In any case, the days of strongly asserting yourself at any cost are probably over and this may be the norm. If you think about it that way, he’s paying naturally without showing off or putting on airs, and performing completely sincerely. To put it simply, it’s a likable album.

Here I’d like to introduce a brief history of Mamoru Ishida. He was born on May 1, 1978, and he became familiar with jazz under the influence of his father. The first instrument he picked up was the trumpet, but he switched to piano in junior high school after hearing Oscar Peterson. During his high school days, he participated in many jam sessions with the aforementioned Hideaki Hori and others including Satoshi Izumi (guitar) and Shinnosuke Takahashi (drums), and they inspired each other greatly.

After entering university, he also joined many jazz study groups and honed his skills. It was around this time that he started his full-fledged performance career, entering the 2001 Yokohama Jazz Promenade Competition mentioned earlier performing in the band of Yasuo Nishimoto (also sax), and winning the grand prize.

Later, he joined Risk Factor, a group led by Akemi Ota (flute), and played in the groups of Tomonao Hara (trumpet), Seiji Tada (alto sax), Miyuki Moriya (alto sax), and others. His musical partners included Mabumi Yamaguchi (tenor sax), Takao Uematsu (tenor sax), Tomoki Takahashi (tenor sax), Akira Omori (alto sax), Joh Yamada (also sax), Shinobu Ishizaki (alto sax), Yochi Kobayashi (drums), Masahiko Osaka (drums), Dairiki Hara (drums), and Gene Jackson (drums).

On the club jazz front, Ishida played on Jill-Decoy’s albums II and IV, as well as Hit The Road by Taichiro Kawasaki, a trumpet player he met through their participation in the group Ego-Wrapping. The members of Jill-Decoy had actually been musical acquaintances for a while, meeting at jam sessions and such since around 2001 with many opportunities to play together.

This is Mamoru Ishida’s second album as a leader, about four years after his previous recording Iemanro. Ishida’s band had changed in those four years, from a piano trio to a one-horn quartet, with this recording featuring Ishida with Mike Rivett (tenor sax), Show Kudo (bass), and Ko Omura (drums). This band started in 2010 when Ishida was playing in Tomonao Hara’s band at Ochanomizu Naru, and the visiting Rivett and Omura sat in with the band. Rivett and Omura had played together many times over the last three years, and have also known Kudo since 1997 when they went to Otaru (Hokkaido, Japan) to attend the workshop of guitarist Koichi Hiroki.

I’ll briefly touch on the profiles of these three members. Mike Rivett is originally from Australia, moved to New York, and is now back in Australia, based in Sydney. He graduated from the Manhattan School of Music where he studied under George Garzone (tenor sax). He is active worldwide in genres from straight-ahead jazz to experimental music, dance music, and beyond.

Show Kudo started on electric bass at the age of fifteen and began to play double bass when he discovered jazz while attending university. In 1997, he moved from Hokkaido to Tokyo to join the Koichi Hiroki group and performed together with Terumasa Hino (trumpet), Kei Akagi (piano), Tetsuro Kawashima (tenor sax), and others.

Ko Omura was raised in the United States, studied classical piano from a young age, and started playing drums in high school. Later, he studied at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music in Australia under Mike Nock (piano) and Judy Bailey (piano). While in Australia, he actively participated in embassy events and Japanese and Australian cultural exchanges, and through these activities met Rivett and began performing together. It was through Omura that Ishida got to know Rivett.

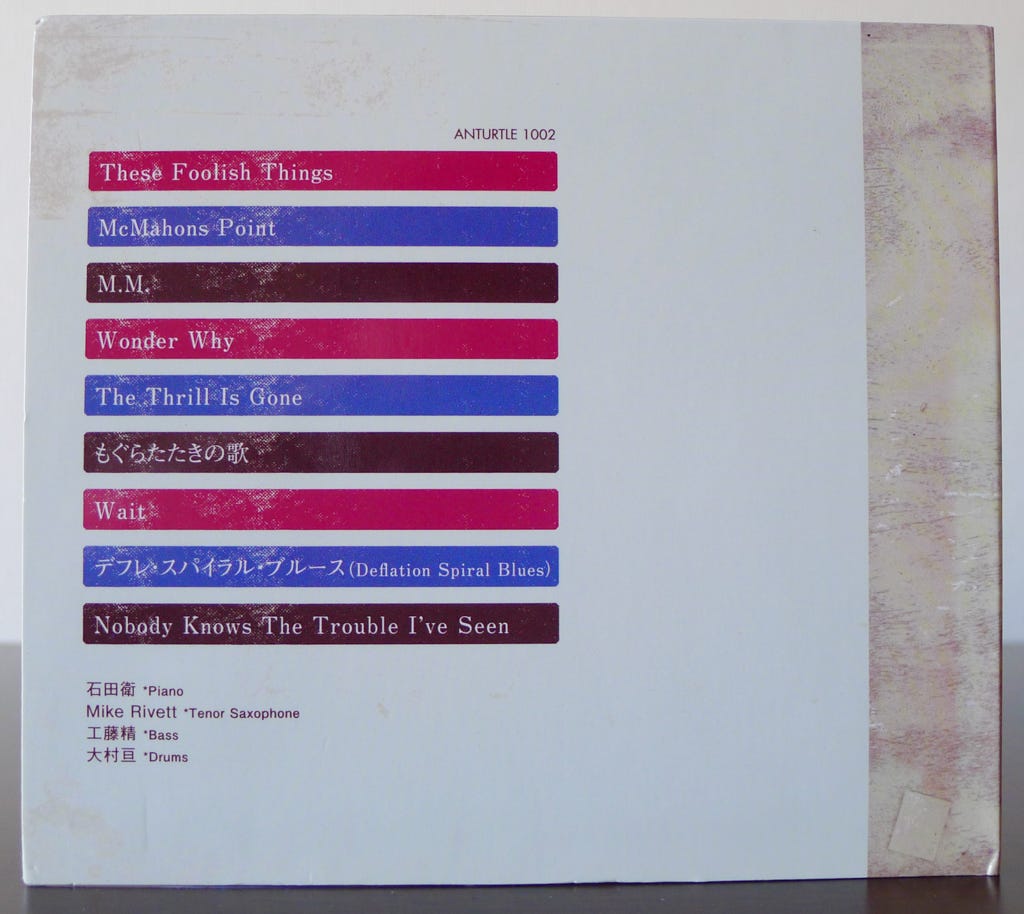

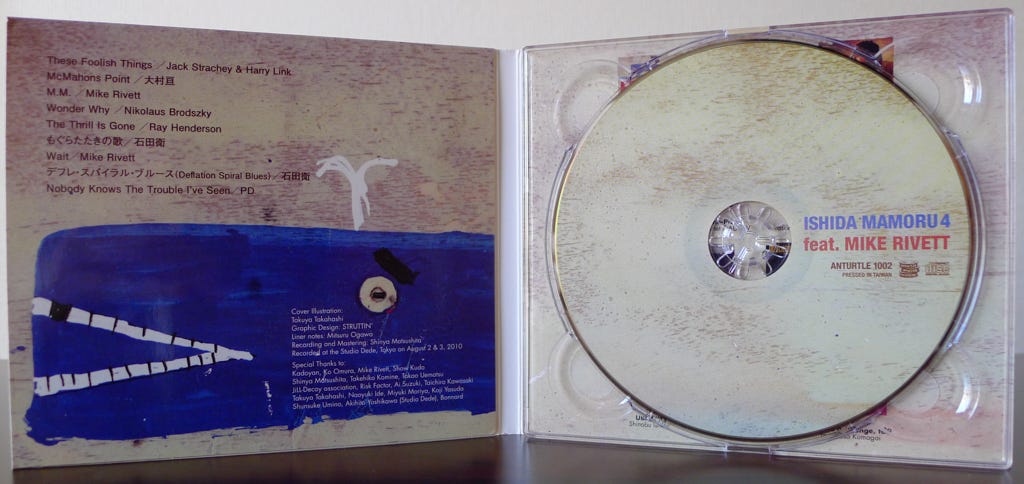

Original compositions on this album include “The Whack-A-Mole Song” and “Deflation Spiral Blues” by Ishida, “McMahons Point” by Omura, and “M.M.” and “Wait” by Rivett. “McMahons Point” refers to a scenic coastal location in Sydney, and “M.M.” are the initials of a certain bourbon brand. In general, Ishida avoids songs that are too complicated or difficult to hum along with, but chose to play “M.M.” because he liked its strange atmosphere.

“The Thrill Is Gone” is a widely known standard, originally adapted into a 1930s musical production and sung by Carmen McRae and others. The song was composed by Ray Henderson and shares the same name as a famous B.B. King hit written by Roy Hawkins. “These Foolish Things” is a 1930s song from the British musical Spread it Abroad, sung by Ella Fitzgerald and others. “Wonder Why” is a piece by Russian composer Nicholas Brodszky, performed by Milt Jackson and others. “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” is an American folk song, especially well-known as a gospel song. In jazz, it’s probably most known for being sung by Louis Armstrong.

As far as Ishida’s compositions and as with his previous work, the unique naming of his songs catches the eye. According to him, he chooses the names quite randomly, and the appeal of instrumental songs without lyrics means no meaning is attributed to them by words. Many songs have titles without much meaning. It seems that having a title without a limited meaning allows the listener to freely imagine what the song means. By the way, the name “The Whack-A-Mole Song” comes from the melody, which seems to have a falling-down rhythm, reminiscent of the whack-a-mole game. While “Deflation Spiral Blues” seems to refer to Japan’s current economic situation, it turns out it’s actually a reference to a professional wrestler’s special move that appeared in a joke comic book called Cromartie High School. Incidentally, that special technique is such a rare move that it doesn’t appear in the comic even once.

Although his debut featured a piano trio, Ishida has performed in many different group formations, and he says that playing together with horns is very fun and exciting. The sound of a horn influences him and brings out aspects of Ishida’s performance that are not present when playing as a piano trio. It seems that the sound that rings in his head is often that of the tenor saxophone, and this tenor saxophone sound may be the instrument closest to his own voice.

Also, Rivett and Omura have mainly worked overseas, and there is a different sensitivity as compared to Japanese players. When I shared my impression with Ishida, he seemed to agree and said in addition you may sense that in the melodic and rhythmic intonation. And, possibly the different environments and languages in which they were raised results in finding beauty in different ways.

Ishida arranged all of the music aside from Omura’s and Rivett’s compositions. Basically, Ishida decided on the overall flow of each song and the order of solos, leaving the individual improvisation and such to each player, with each player’s performance inspiring one another’s playing. On “The Thrill Is Gone”, the melody statement is not played even once, a concept seemingly hinted at by Lee Konitz on his album Motion. “Deflation Blues” was performed with Ishida deciding on just the solo order, that the melody would not be played at the start, but at the ending in a wicked mood.

Although this is a work by Ishida as leader, the other members all have plenty of room in the spotlight. It’s a band where all four members have a high degree of equal participation and freedom. Of course, since all are professional musicians, none cancels out any partner’s performance, and when playing individually each pays attention to the overall balance. While this band had only performed live five times before this recording, there’s no feeling of immaturity as a band, with unity present and room to grow in the future.

Owing to his experience in a variety of performance situations, Ishida himself has become more sensitive to chord subtlety. When playing in larger ensembles, he considers his individual role, what he should add, or what is better to be left out. This can be said to be a point in which Ishida has grown both as a musician and as a person in the previous four years since his last album.

As for a musical analysis of Ishida’s and the other musicians’ performances, expressions, and so forth, going further than this may become a nuisance to Mamoru Ishida fans and listeners, so I’d like to avoid that. As Ishida says, I think it’s better to let people listen freely without being bound by a limited impression.

Finally, as an alternative, I’ll add some information about the recording method. Ishida is quite an analog record enthusiast with a strong commitment to audio quality and recording. For this recording, all members were located in the same room with microphones placed in front of each instrument, allowing the sound of the other instruments to become wrapped up in one’s sound. With this method, each mic picks up a little sound from the other instruments to create a sense of unity and distance, and so the volume balance of the performance itself becomes very important. It seems there were no problems with that for the recording.

Furthermore, another important point was to record two tracks directly onto 1/2-inch tape. The 1/2-inch tape itself has characteristics of a warm and slightly warped sound, something that Ishida also finds appealing. Since it is recorded directly to two tracks, the modern system of punching in to make corrections afterward is not possible, which conversely adds the benefit of creating a sense of tension in the performance. (This used to be a standard recording style, and is a style still favored by many jazz musicians today.)

The microphone used to capture the piano sound is a 1930s Westrex ribbon mic. This is an old type that Ishida chose for its mellow recorded sound. Rather than having a wide stereo position with each instrument’s sound expanding to the right and left, the drums are set to the left, the bass and piano are in the center, and the sax is set to the right. Also, there is very little reverb, resulting in a fairly dry sound being produced.

Ishida Mamoru 4 feat. Mike Rivett by Mamoru Ishida

Mamoru Ishida - piano

Mike Rivett - saxophone

Show Kudo - bass

Ko Omura - drums

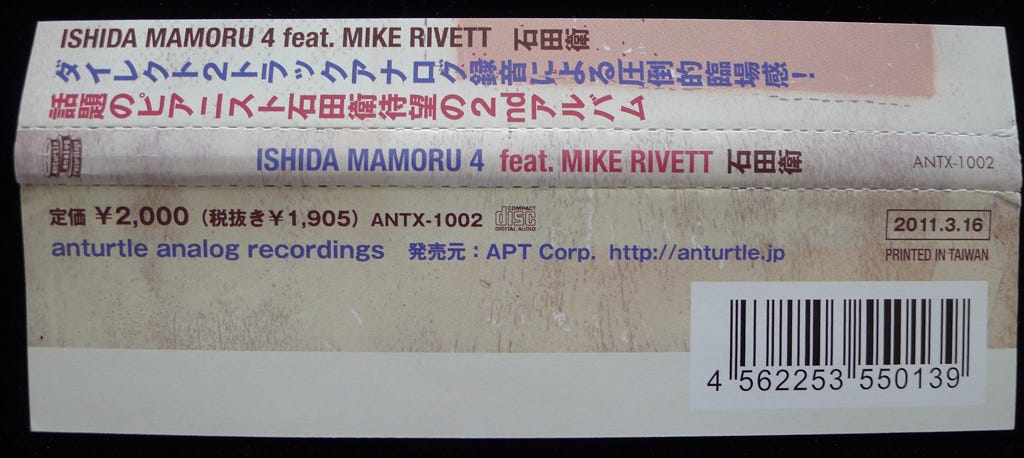

Released in 2011 on Anturtle Analog Recordings as ANTX-1002.

Japanese names: Mamoru Ishida 石田衛 Show Kudo 工藤精 Ko Omura 大村亘

Related Albums

Miyuki Moriya: Cat’s Cradle (2010)

Ko Omura: Introspect (2011)

Keisuke Nakamura: Humadope (2014)

Daiki Yasukagawa Trio: Trios II (2015)

Fumika Asari: Introducin' (2020)

Audio and Video

Mamoru Ishida playing a duo version of “Wonder Why”, track #4 on this album

Excerpt from “McMahons Point”, track #2 on this album: